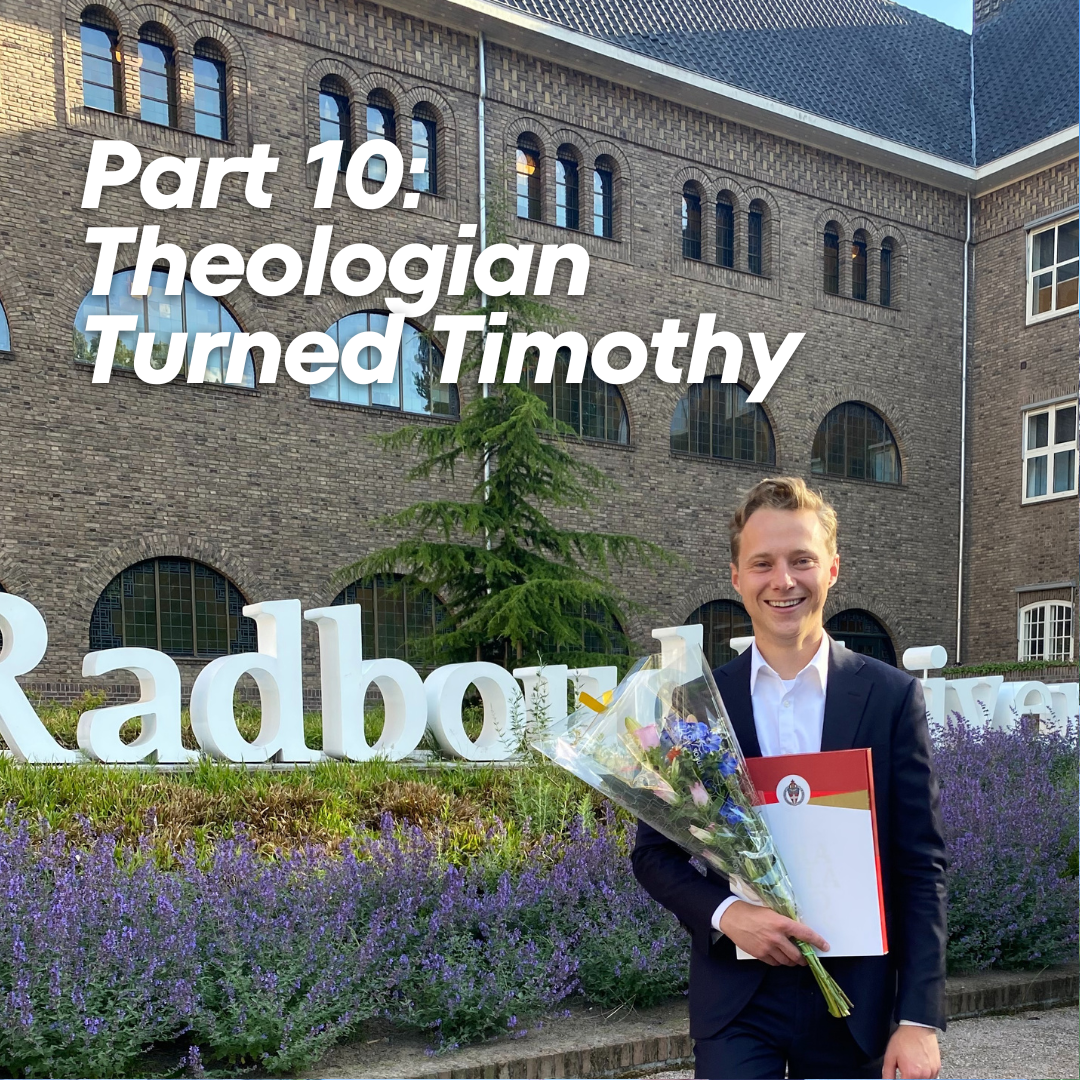

Part 10: Theologian Turned Timothy

I crawled out the window and ran into the woods. I had to make up all the words myself. The way they taste, the way they sound in the air. I passed through the narrow gate, stumbled in, stumbled around for awhile, and stumbled back out. I made this place for you. A place for you to love me. If this isn’t a kingdom then I don’t know what is.

— Richard Silken

A man knows he has found his vocation when he stops thinking about how to live and begins to live.

― Thomas Merton