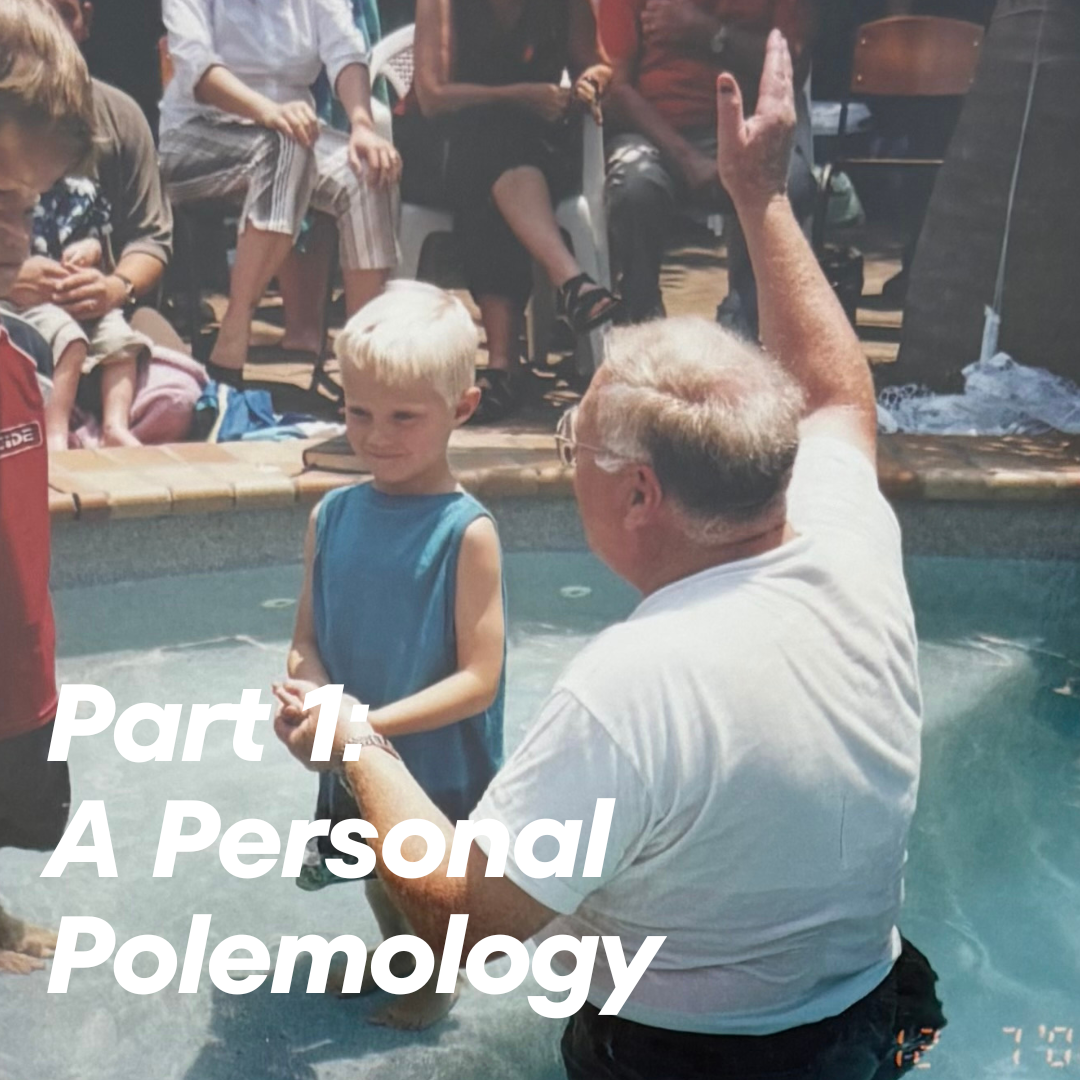

Part 1: A Personal Polemology: Three Vignettes from a Decade-Long Holy War

You say that I showed you the light,

but all it did in the end

was make the dark feel darker than before.

— Lucy Dacus

How wonderful to be hidden,

how terrible not to be found.

— D.W. Winnicott